Monday, October 23, 2006

Skilling Gets 24 Years for Fraud at Enron

`

Former Workers Tell of Hard Times Over Lost Jobs, Retirement Savings

By Carrie Johnson

Washington Post Staff Writer

Monday, October 23, 2006; Page A01

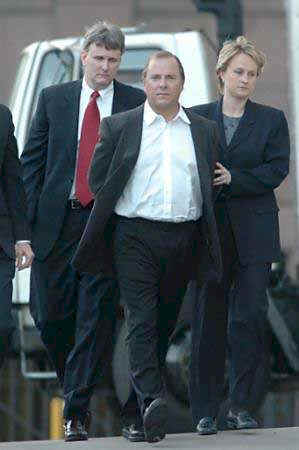

Former Enron CEO Jeff Skilling, goes to the pokey Monday, Oct. 23, 2006 in Houston.

Jeff Skilling leaving courthouse AFTER sentencing!

HOUSTON, Oct. 23 -- Jeffrey K. Skilling, the brash former chief executive of Enron Corp., was ordered to serve 24 years and four months in prison Monday after an emotional court hearing in which he watched a series of former employees blame him for the fraud at the heart of the company's collapse.

Skilling's face reddened but he remained impassive as he listened to five angry and tear-choked workers tell the court about their difficulties since losing their jobs and retirement savings after the Houston energy company hurtled into bankruptcy five years ago.

Dawn Powers Martin, who worked at the company's credit union for 22 years, called Skilling a "liar, a thief and a drunk" who "cheated me and my daughter out of our retirement."

When asked to make a statement, Skilling professed remorse but he spoke with the most passion when he vowed to appeal. "I am innocent of every one of these charges," he told the court.

U.S. District Judge Simeon T. Lake III rejected a defense bid that would allow Skilling to remain free while he contested his conviction in May on 19 charges of fraud, conspiracy and insider trading. Skilling was not allowed to leave the courthouse until authorities fitted him with an electronic ankle bracelet that officials will use to monitor his movements while the Bureau of Prisons determines where he will serve his term. He has asked to be sent to a medium-security prison in Butner, N.C.

Under federal rules, Skilling, 52, must serve at least 85 percent of his sentence, which means he would not be released for more than two decades, when he will be in his 70s. Lake could have imposed a stiffer penalty. Skilling's sentence is second only to the 25-year term given to WorldCom Inc. founder Bernard J. Ebbers, whose company also collapsed during an accounting fraud that rocked investor confidence and prompted Congress to pass corporate accountability legislation in 2002.

"The Enron case is as large and as serious as any other fraud in this nation's history," prosecutor Sean M. Berkowitz told the court.

Skilling entered the courtroom arm-in-arm with his wife, former Enron corporate secretary Rebecca Carter, who sat in the first row with Skilling's brother and sister. During the proceeding, Carter cried and frequently bowed her head. Two children of Enron founder Kenneth L. Lay and his defense team were also present, and they comforted the Skilling family members with hugs and pats on the back.

Nine of the jurors in the long-running trial, including three alternates, also showed up as spectators, looking on from a back row as the hearing played out. Later, they said they supported the judge's decision, as did the former employees who testified.

Skilling's emotional state has been delicate since he left Enron. Over eight days on the witness stand during the trial, Skilling described his spiral into drinking and depression as Enron began to sink under the weight of its financial problems. After he was indicted, he twice had contact with police related to his alcohol consumption, most recently last month.

Monday afternoon, he told reporters that he had suffered over the past five years, at times, he said, even wishing he had injured himself more seriously during a hiking trip.

"There are times I'd say, 'God, I wish I'd died,' " he said.

The judge acknowledged that Skilling had helped transform Enron into one of the nation's largest companies. Skilling and his lead lawyer took time to underscore their contention that Enron collapsed not because of fraud, but because the market lost confidence in the company months after his abrupt resignation in August 2001. That caused creditors to demand immediate payment for their loans, creating a cash crunch the company could not withstand.

Skilling enlisted friends, including his administrative assistant of two decades, to speak on his behalf. "I don't consider myself a victim of anything other than my shortsighted [investment] decisions," said the assistant, Sherri Sera. She called Skilling a "visionary" who "revolutionized" the energy industry. As she returned to her seat, she embraced Skilling's wife.

But Lake said Skilling's good works did not outweigh that he had "imposed on hundreds if not thousands of people a life sentence of poverty."

As part of the resolution of the case, Skilling also agreed to turn over what his lawyers called the "overwhelming majority" of his assets, about $45 million, including the proceeds from the sale of his Mediterranean-style mansion, to employees who lost more than $1 billion with Enron's demise. His lawyers at O'Melveny & Myers LLP are to receive $15.5 million to pay suppliers and to cover some fees, estimated at $30 million. In what analysts have called the highest-ticket criminal defense in history, the firm already has collected $40 million in cash from Skilling and his insurance policies to defend criminal and civil cases.

Under the federal sentencing guidelines, Skilling could have received more than 30 years in prison. Instead, the judge chose a term on the lower end of the range. The judge scuttled a defense request to shave 10 months off the prison term, a move that would have made Skilling eligible for a low-security facility with fewer restrictions than the medium-security prison where he ultimately will reside.

Skilling's term is by far the longest of any won by the Justice Department's Enron Task Force, which announced late Monday that it was closing its doors. Former finance chief Andrew S. Fastow, who admitted to siphoning millions of dollars from the energy-trading company but ultimately cut a deal with prosecutors and testified against Skilling, got a six-year sentence. Lay, the founder of Enron and also a defendant in the case, died of heart disease in July, only weeks after he and Skilling were convicted by a jury.

Lake threw out Lay's conviction last week, citing a legal precedent that comes into play after a defendant dies before he completes the appeals process. On Monday, prosecutors said they had filed a civil lawsuit against Lay's estate seeking to recover $2.5 million used to pay the mortgage on his Houston penthouse condominium, $10 million from a family trust and $22,000 from a bank account.

Outside the courthouse, Skilling met throngs of reporters and camera crews. Wearing a tracking device underneath his navy suit, he waxed about Enron's past business prospects and talked about the "nightmare" his life had become. He said he felt horrible about the victims of Enron's collapse, but added that he had not broken the law, despite the aggressive prosecutors, the demonizing media reports and the resounding jury verdict.

"In the Inquisition, only about 10 percent of the people held out," Skilling said. "I can tell you it ain't fun."

No smoking guns, but there were smoking cannons!

It was a very strong case and he'll be in jail until his late 70's!